Wordymology is a series in which the editors at The Free Dictionary explore the origins of the names of things. Down in History: 11 names remembered for all the wrong reasons.

History smiles on those historical figures whose names live on in the title of their invention or other positive contribution to humanity. But it frowns on thoseunfortunate individuals whose names have become forever associated with things negative. Here's how it happened to these 11 eponymous personages.

Boycott

The boycott is named for its first unlucky recipient, Charles C. Boycott. Boycott was serving as an English land agent in Ireland when Irish nationalist leader Charles Parnell urged his supporters to abstain from patronizing or working for any landlord who would not lower their rents. In 1880, Boycott refused to lower rents, and, yep, they boycotted Boycott.

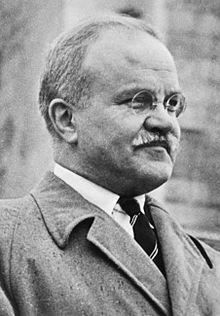

Molotov cocktail

When young Vyacheslav Skriabin joined the Communist Party and changed his last name to evade the imperial police, it was a decision with explosive consequences. For his new surname, he chose the Russian word for “hammer”—Molotov (not really a name you give yourself, but OK). But he did not create his namesake firebomb or even bestow his name upon it. No, the first "Molotov cocktail" was actually being thrown at him (at least in spirit). When the Soviet Union invaded Finland in 1939, Finnish troops retaliated with makeshift bombs that they called Molotovin koktaili. Molotov, serving as the Soviet Commissar of Foreign Affairs at the time, had been instrumental in bringing about the invasion and so drew the Finns’ ire (and fire).

Shrapnel

“Shrapnel” is such a perfect name for the bits of an exploded bomb that you couldn’t be blamed for guessing that it comes from some Germanic root meaning “fragment.” But no, it comes from a proper name—British general Henry Shrapnel, who dropped a bomb on modern warfare when he invented his eponymous shrapnel shell. Designed to explode in midair and strike a wide area with its fragments, Shrapnel’s creation was adopted by the British Army in 1803.

Dunce

The first “dunce” was really a Duns. John Duns Scotus was a medieval scholar and theologian who was especially influential in Catholic theology. He even founded a school of thought called “Scotism” that sought to separate philosophy from theology. In the Renaissance, however, humanists began to ridicule and dismiss his teachings, and his reputation suffered. His followers were derided as “Dunses” or “Dunsmen,” leading to the “dunce” we know today, and relegating Duns to the corner of history.

Typhoid Mary

Although Mary Mallon never exhibited symptoms of typhoid fever herself, she transmitted the illness to as many as 50 people while working as a cook in early 20th-century New York City. Quarantined for years, she became known as “Typhoid Mary.” Her nickname lives on as a shorthand way to refer to someone who is deemed to be a carrier of anything unpleasant, not just illness.

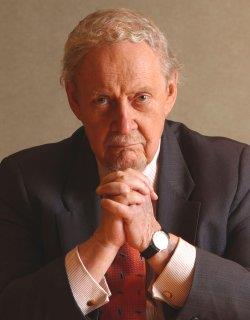

Bork

“Getting borked” sounds unpleasant enough, even without knowing that it means being systematically attacked in the media, especially to block one’s appointment to some public office. Judge Robert H. Bork endured such a fate in 1987 after US President Ronald Reagan nominated him to the Supreme Court. Bork’s nomination was ultimately blocked, in part due to a strong media campaign against him by those who opposed him, and the word “bork” was born.

Chauvinism

Although “chauvinism” today is commonly associated with sexism (as in “male chauvinism”), that’s a newer use of the word, born of the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s. The word “chauvinism” actually dates back to the 19th century and originally referred to Napoleon’s overzealous followers and their unwavering patriotism. French soldier Nicolas Chauvin was said to be one such Napoleonic devotee, though he is most likely a legendary figure.

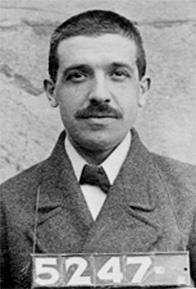

Ponzi scheme

Even before attempting the scheme that now bears his name, Charles Ponzi had racked up a serious rap sheet, including convictions for check forgery and smuggling immigrants. His so-called “investment opportunity” paid out initial investors with funds supplied by later ones, a tactic that eventually fell apart (surprise!) in 1920 to the tune of $7 million in investor losses and federal and state charges for Ponzi. Ponzi wasn’t even the first person to run such a scam, but his name is forever attached to it.

Bowdlerize

Critics of English editor Thomas Bowdler wanted to send him packing in 1818 when his heavily edited edition of Shakespeare’s works (reassuringly titled Family Shakespeare) was released and scorned for its seemingly excessive, prudish edits. Since then, to remove objectionable content from something has been to “bowdlerize.” It may be cold comfort to Bowdler, but his Family Shakespeare has been reprinted many times.

Guillotine

In 1789, as the chaos of the French Revolution gripped France, French physician Joseph Ignace Guillotin addressed the French National Constituent Assembly to urge them to adopt a more humane method for executions, proposing mechanical beheading as a replacement for hanging or other methods. The Assembly heeded his suggestion, and such a device was devised by another doctor, Antoine Louis, and first used in 1792. Louis’s contraption initially bore his name and was called the louisette or louison, but it soon became known as the “guillotine,” thanks to Guillotin’s famous speech. After Guillotin’s death, his family attempted to have the name of the device changed, but the association could not be severed.

Gerrymander

American politician Elbridge Gerry had an illustrious political career. He signed the Declaration of Independence! He served as Vice President under James Madison! But he’s best remembered for one particularly slimy political ploy. In 1812, while serving as governor of Massachusetts, Gerry took drastic measures to try to keep his party in power by signing a bill that allowed voting districts in his state to be revised in a way that would benefit his party. One such district formed a grotesque, salamander-like shape that was dubbed a “gerrymander,” a term his critics used to torpedo his chances of reelection. But as if becoming synonymous with dirty politics wasn’t bad enough, Gerry’s name is usually mispronounced—at least according to his ancestors, who insist it should be said not with a soft G sound (like “Jerry”), but instead with a hard G sound (like “Garry”). Serves him right.